Season 3, Episode 6

listen on Spotify

listen on Apple Podcasts

Emma and Christy discover Margaret Watts Hughes’s beautiful ‘voice figures’, a series of images made through the direct action of her voice between 1885 and 1904. In this episode, we discuss the earliest sound recordings, scientific ‘instruments’ (it’s a pun), cat pianos, severed ears, occult science, seaweed scrapbooks, women in STEM, logos and the word of God, visualising the invisible, the Little Mermaid, clairvoyant research, ‘thought forms’ and the death agonies of pigeons, science and feeling, and why sonic media is always already haunted.

MEDIA DISCUSSED

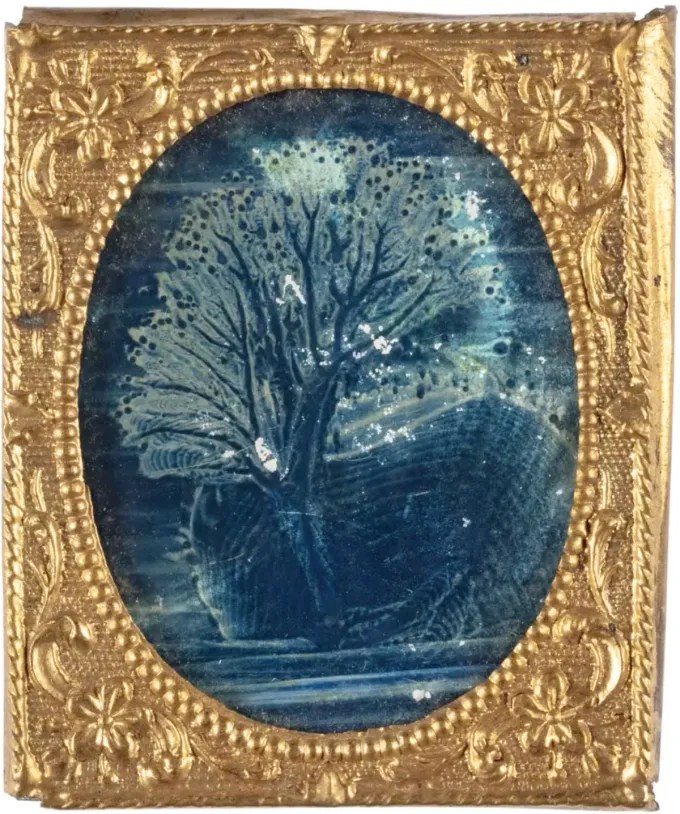

Margaret Watts Hughes, Impression Figure (c. 1904), courtesy of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery

Margaret Watts Hughes, Tree Form (before 1904)

Portrait miniature example: Nicholas Hilliard, Queen Elizabeth I (1572)

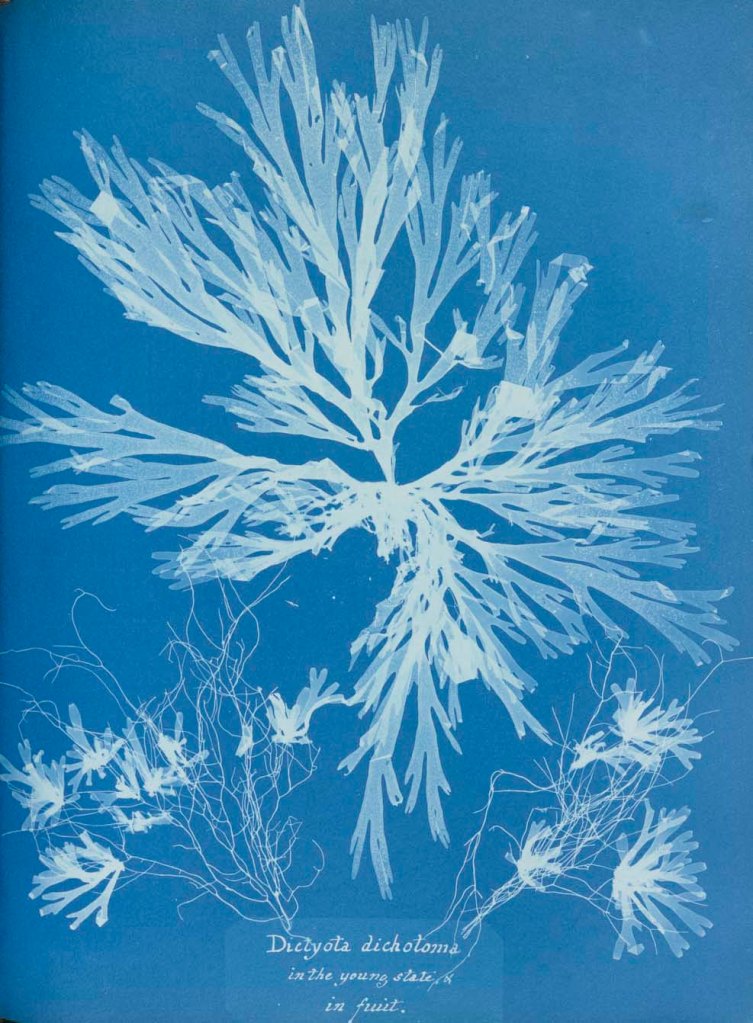

Anna Atkins, Dictyota Dichotomy (Forkweed) (1848)

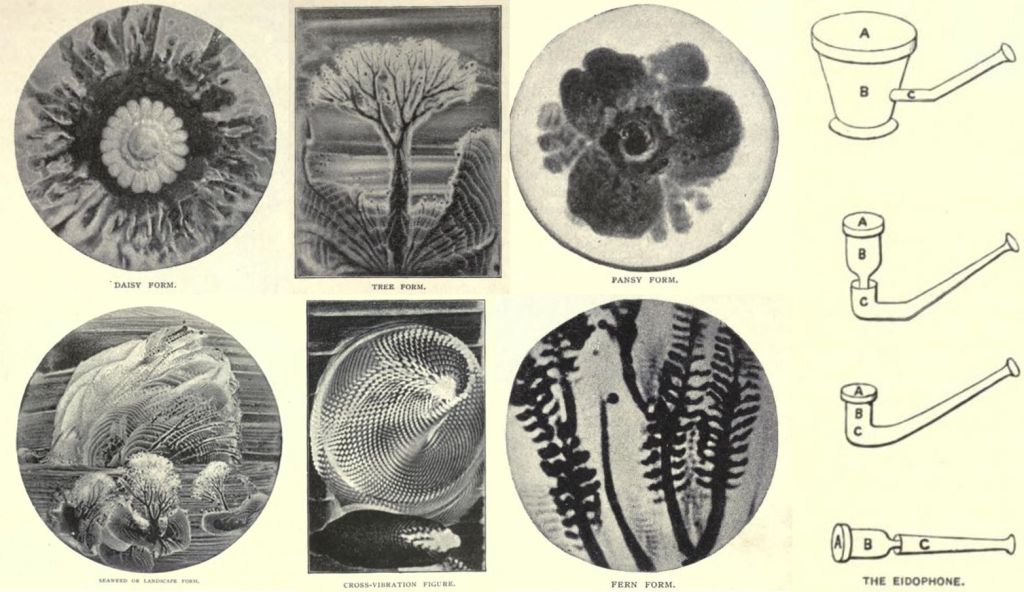

Illustration from Margaret Watts Hughes, ‘Visible Sound: Voice-Figures’, Century Magazine (1891)

Margaret Watts Hughes’s eidophone

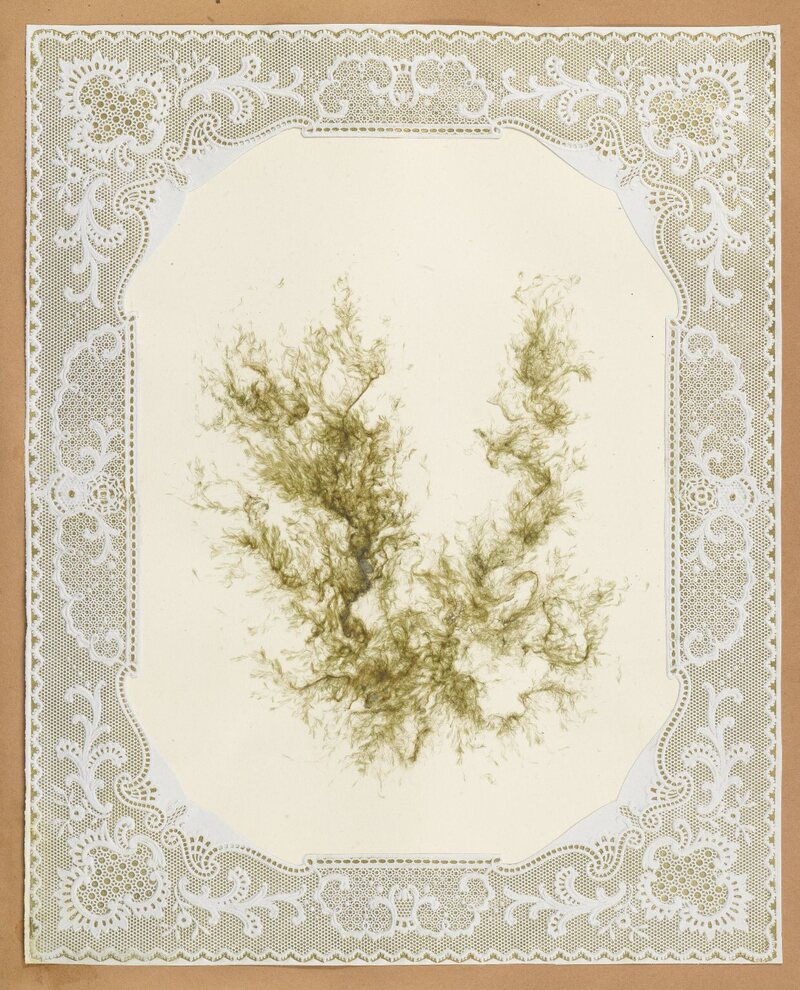

Example of page from an algae or seaweed scrapbook by Eliza A. Jordan (1848)

Georgiana Houghton, Glory Be to God (1864)

‘Phonautography of the human voice at a distance’ (lines of recorded sound generated by Scott de Martinville’s ‘phonautograph’, 1857)

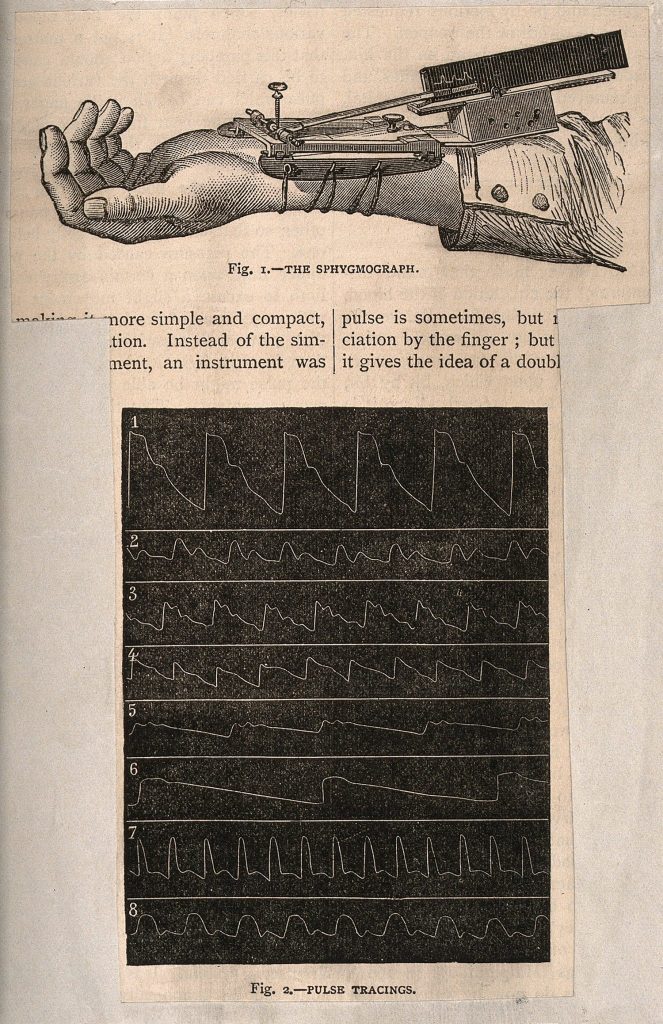

The graphic method: Étienne-Jules Marey’s sphygmograph (a predecessor of modern EKG machines, 1881)

Louis Bertrand Castel’s ‘ocular harpsichord’ (1725)

Isaac Newton’s colour spectrum and musical scale analogy (1675)

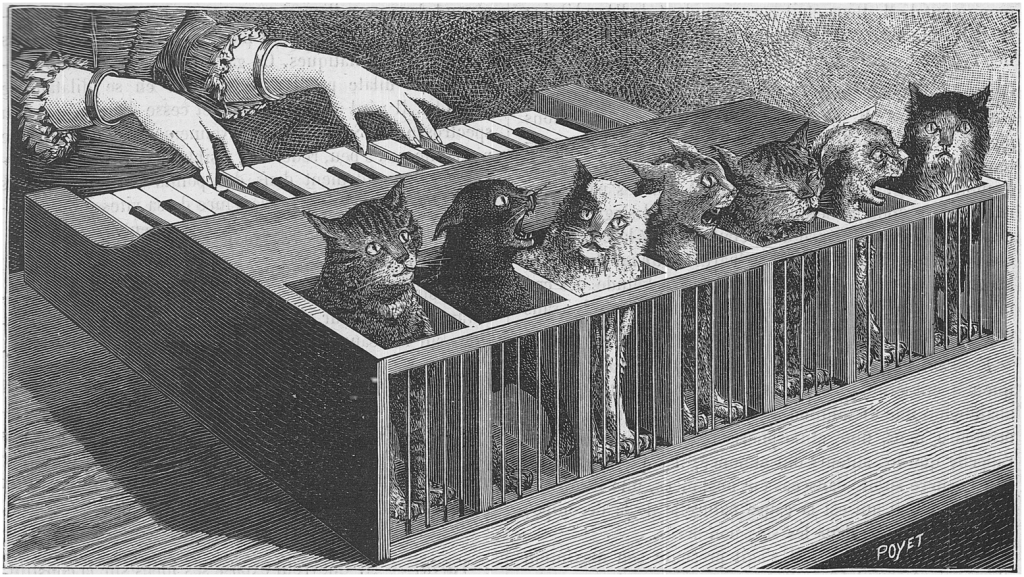

The cat piano (illustration from La Nature, 1883)

The ‘ear phonograph’ of Alexander Graham Bell and Clarence J. Blake (1874), 2018 model by the Science Museum

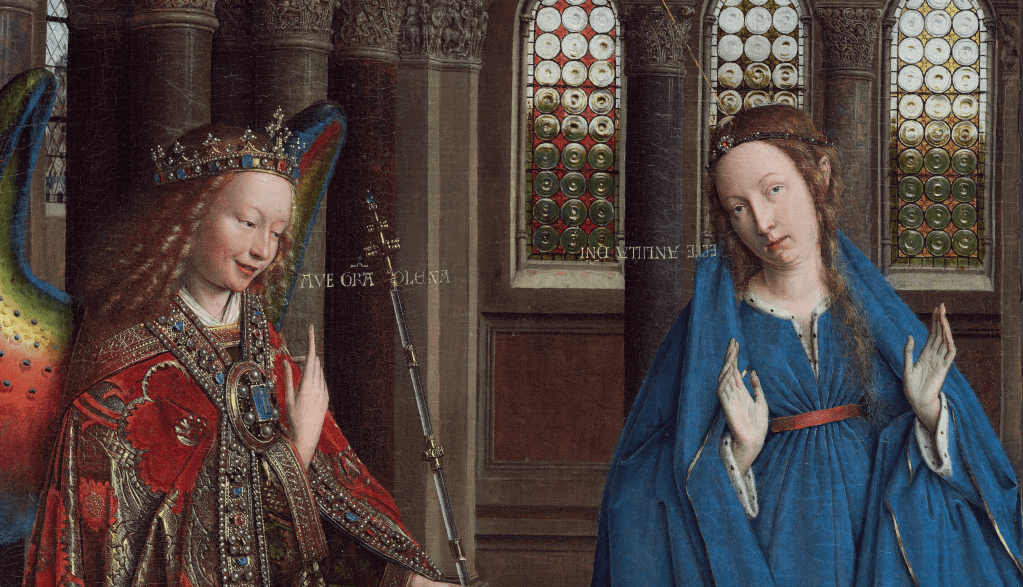

Jan Van Eyck, detail from Annunciation (c. 1434–36)

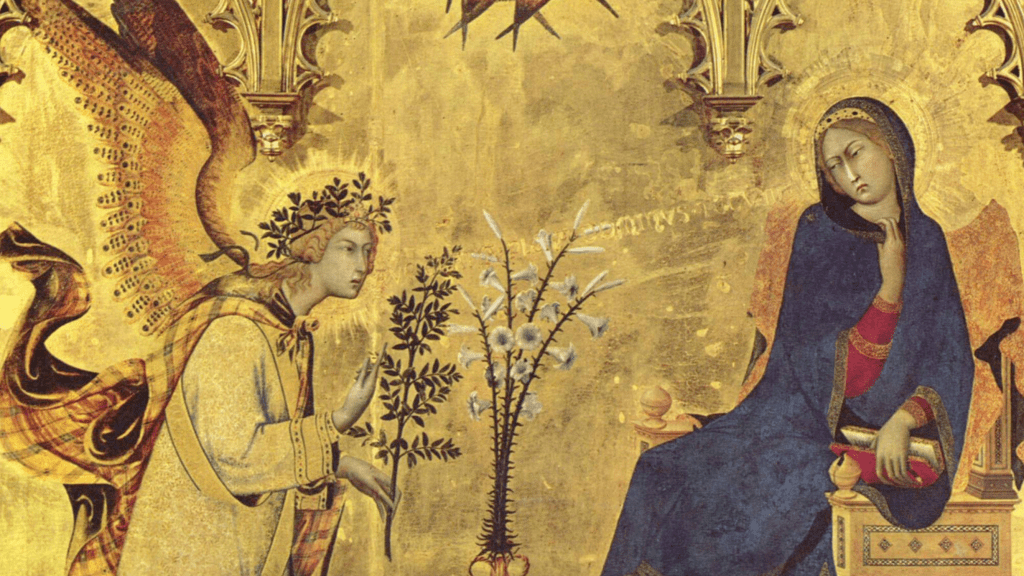

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, detail from The Annunciation showing raised gold lettering (1333)

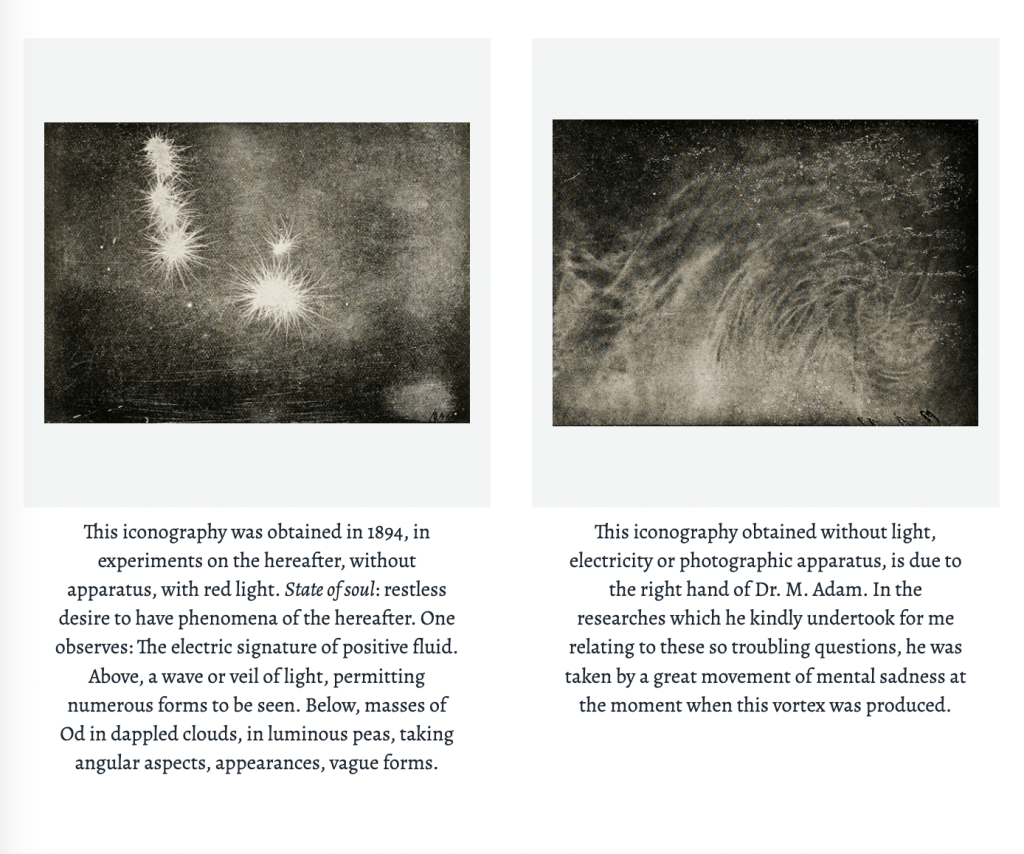

Hippolyte Baraduc, two cameraless photographs showing various feelings (‘restless desire to have phenomena of the hereafter’; ‘mental sadness’), 1894–1913

‘The Music of Gounod’, illustration from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Thought Forms (1901)

‘Aspiration to Enfold All’, illustration from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Thought Forms (1901)

‘Radiating Affection’, illustration from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Thought Forms (1901)

‘The Intention to Know’, illustration from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, Thought Forms (1901)

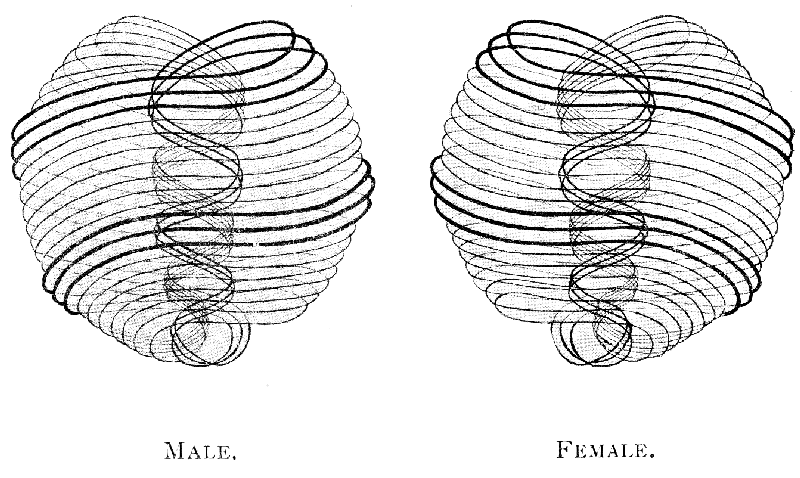

Illustration from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater’s Occult Chemistry (1908)

REFERENCES

Emilie Russell Barrington, ‘Mrs. Watts Hughes’s “Voice Figures” (Letter to the Editor of the Spectator), The Spectator (1889)

Margaret Watts Hughes, The Eidophone Voice Figures: Geometrical and Natural Forms Produced by Vibrations of the Human Voice (London: The Christian Herald Co. 1904)

Rob Mullender Ross] ‘Divine Agency: Bringing to Light the Voice Figures of Margaret Watts-Hughes’, in SoundEffects 8.1 (2019)

Thomas L. Hankins and Robert J. Silverman, Instruments and the Imagination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995)

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1995/1996)

Suzannah Biernoff, ‘Medical Archives and Digital Culture,’ Photographies 5, no. 2 (September 2012): 179–202

Henry Steel Olcott, ‘Mrs. Watts Hughes’ Sound-Pictures’, The Theosophist 11.132 (September 1890), pp. 665–670

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, Thought Forms, 2nd ed (Bradford: Percy Lund, Humphries & Co., 1905)

Sumangala Bhattacharya, ‘The Victorian Occult Atom: Annie Besant and Clairvoyant Atomic Research’ in Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age, ed. by Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2016)

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, Occult Chemistry: Clairvoyant Observations on the Chemical Elements ( (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1908)

Coreen McGuire, Measuring Difference, Numbering Normal: Setting the Standards for Disability in the Interwar Period (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020)

FURTHER READING

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2010)

Tom Everett, ‘Writing Sound with a Human Ear: Reconstructing Bell and Blake’s 1874 Ear Phonautograph’, The Science Museum Journal (2018)

‘Imaging Inscape: The Human Soul (1913)’, Public Domain Review (2021)

Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Voice, Sound, and Aurality in the Arts (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001)

Rob Mullender Ross, ‘Picturing a Voice: Margaret Watts Hughes and the Eidophone’, in Public Domain Review (2019)

Simone Natale, Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2016)

Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham, Duke University Press, 2000)

Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, Duke University Press, 2003)

Jonathan Sterne, ‘The Ear Phonautograph’, in Unsound, Undead, ed. by Steeve Goodman, Toby Heys, Eleni Ikoniadou (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019)

Shelley Trower, ‘Libraries of Voices’ in Unsound, Undead, ed. by Steeve Goodman, Toby Heys, Eleni Ikoniadou (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019)

Follow our Twitter @drawingblood_

Follow our Blue Sky @drawingbloodpod.bsky.social

‘Drawing Blood’ cover art © Emma Merkling, image courtesy of the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgeons

All audio content © Emma Merkling and Christy Slobogin

Intro music: ‘There Will Be Blood’ by Kim Petras, © BunHead Records 2019. We’re still trying to get hold of permissions for this song – Kim Petras text us back!!